Cover Story

Leopold’s ‘Magic’ Words Enchant a Wider Audience

Digitized and transcribed, the journals that served as the foundation for Aldo Leopold's A Sand County Almanac are now more accessible than ever before.

It’s a rare opportunity for the public to glimpse the original, handwritten notes and journals of an influential environmentalist, let alone one as renowned as Aldo Leopold. Or, at least, it used to be a rare opportunity. Thanks to a collaboration between UW and the Aldo Leopold Foundation, and to the tireless efforts of dozens of dedicated volunteers, Leopold’s famous “Shack Journals” are now more accessible than ever before.

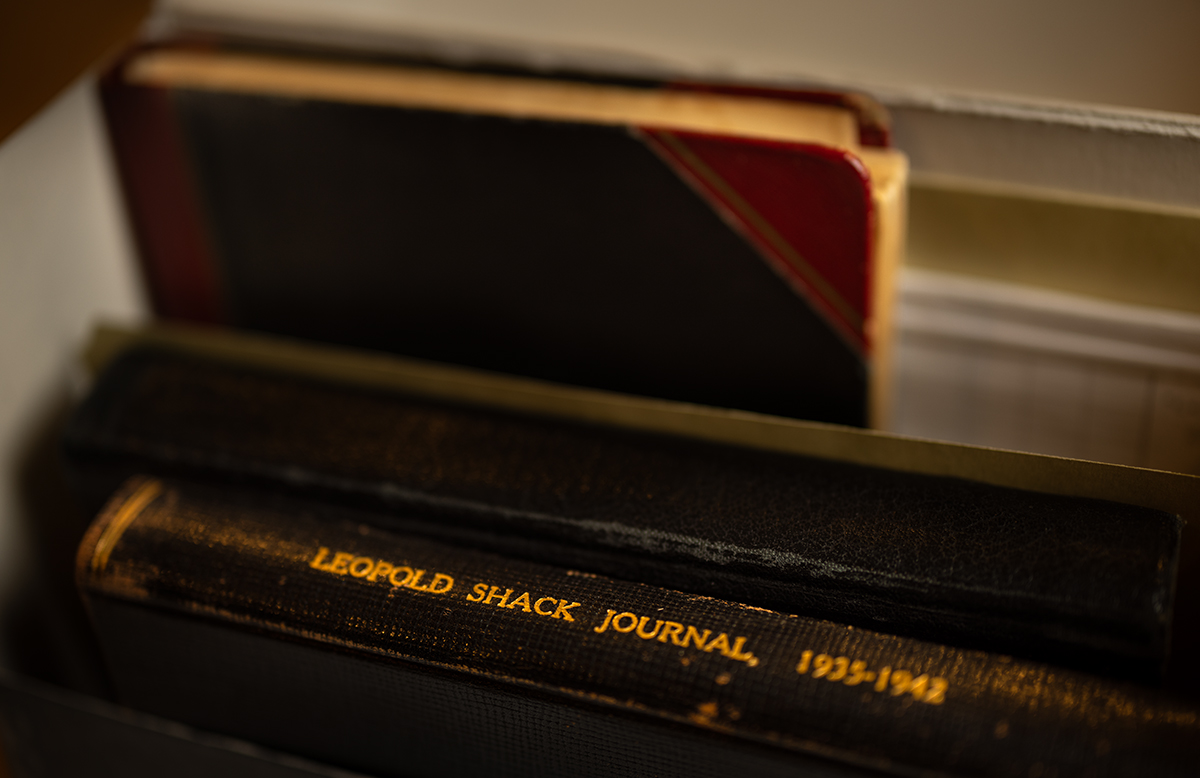

The original Shack Journals — which contain the tight, penciled script of Leopold’s detailed observations that inspired the essays he later collected in A Sand County Almanac — are housed safely in the UW archives. For decades, anyone who wanted to access the journals had to schedule time to view them in a reading room and carefully scan, page by page, for the reference they needed.

In 2007, the UW Digital Collections Center (UWDCC) began a multi-year process of digitizing all the material in the Leopold Collection so each item could be viewed online. It was a significant step toward greater accessibility. But, years later, staff from UWDCC, UW Archives and Records Management, and the Aldo Leopold Foundation took it even further. In 2022, they recruited a passionate group of volunteers to transcribe all 1,100 handwritten pages of the Shack Journals, making it far easier for researchers, educators, and the public to read and search Leopold’s original writings.

Leopold’s connections to Wisconsin, UW, and CALS are strong. He spent years as a professor of wildlife management in the college (the first position of its kind), and his land restoration efforts at the UW Arboretum inspired personal restoration projects carried out at the Leopold Shack on his family’s land near Baraboo, Wisconsin. The shack and its surrounding lands, now a National Historic Landmark, remain a hub for ecology and conservation efforts to this day.

Stan Temple was just a young academic when he took on the same professorship Leopold held. Temple quickly connected with the Leopold family, forming bonds through a shared passion for phenology, the study of seasonal phenomena. Leopold took detailed records on the changing seasons in the Shack Journals, and they have been a constant reference for Temple.

“In my capacity as a professor at the University of Wisconsin — and after my retirement as a senior fellow at the Aldo Leopold Foundation — I have used the Leopold Collection a lot,” Temple says. “But it was always a challenge because so much of the important, raw data that I was looking for was handwritten, and it couldn’t be searched easily.”

For example, say someone was curious about when the first spring wildflowers began blooming in 1940, or they wanted to compare sightings of sandhill cranes during Leopold’s time to more recent observations. Before this project, a person would have had to click through the digitized journals and search every page of Leopold’s handwriting to find mentions. Not anymore.

“Adding the transcriptions is a game changer for research,” says Jill Kambs, production manager at the UWDCC. The digitized text allows users to search within the content of Leopold’s Shack Journals and other items across the entire UWDCC catalog. For example, one can now search for not only how many times Leopold references chickadees in the Shack Journals but also where chickadees are referenced across resources from authors in other collections.

Sharing both the historical records of Leopold’s natural observations as well as his views of the world around him is at the core of the Aldo Leopold Foundation, says executive director Buddy Huffaker. He also notes that the project would not have been possible without the capacity and expertise provided through their partnership with the UWDCC and University Archives and Records Management, which houses the physical copies of the Shack Journals and other pieces of the Leopold Collection.

“It’s an unparalleled insight into this brilliant scientific communicator’s mind and work,” Huffaker says, adding that the journals can be just as significant for people familiar with Leopold’s legacy as they can be for newcomers to his ecological efforts.

And none of it would be possible without the manual work of more than 60 devoted volunteers who know firsthand that it’s one thing to read Leopold’s essays in their final published form, but it’s another entirely to read the handwritten notes and observations that inspired them.

Kei Kohmoto spearheaded the coordination of volunteers while she was a fellow at the Aldo Leopold Foundation. She assigned them journal pages for transcription, instructed them on careful methods, and ensured each transcription was meticulously fact-checked.

Kohmoto was an undergraduate when she first read A Sand County Almanac. For her, reading notes from the Shack Journals, seeing the day-today of Leopold’s life that underlays his grandiose and beautiful essays, is a unique way to engage with Leopold and his environmental framework.

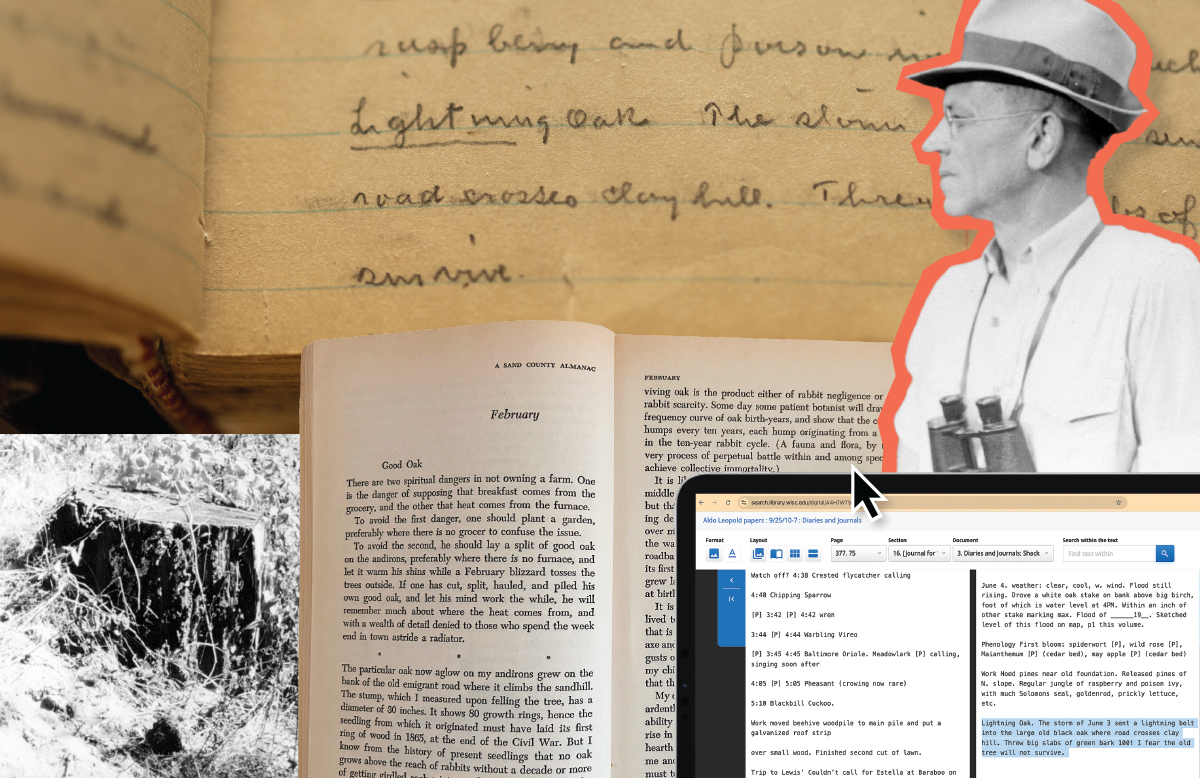

For example, one of Kohmoto’s favorite essays from the almanac is “Good Oak,” a grand allegory that Leopold uses to reflect on the passage of time, history, and changes across landscapes. But in the Shack Journals, the roots of this essay can be traced back to an entry simply noting that lightning struck an oak tree on the property. The event is noted in the entry for June 4, 1943, and it reads, “Lightning Oak. The storm of June 3 sent a lightning bolt into the large old black oak where road crosses clay hill. Threw big slabs of green bark 100 [feet]! I fear the old tree will not survive.” Sawing through the growth rings of that dead tree while making firewood was how Leopold reflected on the passage of history.

Allegory of the Oak

The image collage above contains the original passage (top) from one of Leopold’s Shack Journals, dated June 4, 1943, reads, “Lightning Oak. The storm of June 3 sent a lightning bolt into the large old black oak where road crosses clay hill. Threw big slabs of green bark 100 [feet]! I fear the old tree will not survive.”

Leopold (shown at top right working in the field circa 1947) and his daughter, Estella, later cut the damaged tree down, and photographer Phil Sander captured an image of the stump circa 1948 (lower left). The experience inspired the reflective essay “Good Oak,” which was included in A Sand County Almanac. At bottom is the transcription of the passage (highlighted in blue), as seen on the UW–Madison Libraries website, where one can browse, search, and read transcriptions of the journals, along with digital scans of original pages.

Connecting with Leopold’s materials in this way was magical for more than just Kohmoto. “People would always reply back, letting me know how much they enjoy transcribing it and making sure I let them know if any more opportunities arise,” Kohmoto says.

Kathy Miner was one such passionate volunteer. Miner, who is also a naturalist at the UW Arboretum, found her career path thanks to a college course that assigned A Sand County Almanac as required reading. She recalls being grabbed by Leopold’s rare talent for combining science, data, and discipline with poetic writing.

A passage from the essay “Goose Music,” which originally appeared in a Leopold collection called Round River but was later included in a special edition of A Sand County Almanac, inspires readers to imagine the absence of bird song in an improperly stewarded landscape. It struck a particularly emotional chord with Miner.

Years later, during the digitization of the Shack Journals, Miner was able to read the original manuscripts for that essay. And she was once again immersed in magic when she volunteered to transcribe several pages of the Shack Journals in the latest iteration of the project. On the very first page of her assigned journal section, Miner began transcribing a moment when Leopold’s daughter found, in an owl pellet, the band of a chickadee he had banded for tracking purposes a year earlier.

“I suddenly realized that I was typing, exactly, something that had become part of that last essay in the calendar section of the almanac (essay “65290”),” Miner says.

The simple description of a banded bird preyed on by an owl became enshrined in A Sand County Almanac as the only “evidence of actual murder” a chickadee Leopold witnessed. Seeing the event in the journal entry and then in the essay brings the whole concept to life. It’s not hard to imagine Leopold, poring over his notes, flipping through his journals to choose which details to add to the essays for his now renowned book.

It’s also easy to understand why so many volunteers would want to participate in this project. Now, people don’t have to pour over and flip through the pages. They can type in and automatically find the references they need, the beloved sections they want to reread, and maybe even new discoveries still waiting in the pages.

“[Leopold’s] writing came to my attention at a particularly remarkable point in my life, where it was very meaningful,” Miner says. “I guess I’d like that magic to be able to happen to a lot of other people.”

This article was posted in Features, Healthy Ecosystems, Summer 2025 and tagged A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold, Aldo Leopold Foundation, digital access, Forest and Wildlife Ecology, Leopold Shack Journals, Stanley Temple, UW Archives, UW Digital Collections Center.