Feature

Whither the Children?

With child safety in mind, researchers explore support gaps for farmers' childcare needs.

When you search Google for “family farms,” the dominant images served up show parents and their young children in bucolic agricultural settings, often walking together through verdant or golden fields.

These idyllic family portraits, however, overlook the reality that many farm parents face. Farmwork often involves high-tech equipment, heavy machinery, and large animals. That makes many farms hazardous places — especially for kids.

According to data from the National Children’s Center for Rural and Agricultural Health and Safety, a child dies in an agriculture-related incident about every three days, and around 33 injuries occur per day. Common causes of fatalities include transportation incidents with tractors and ATVs and contact with machinery and animals.

For more than 30 years, farm safety experts have been encouraging farm parents to seek dedicated, off-farm childcare. But rural areas tend to be “childcare deserts,” with few affordable options nearby. That makes childcare a significant challenge and stressor for farm parents.

“Even though these pictures are often used to celebrate agriculture, they also create hardships for the people who are trying to do this work,” says Michaela Hoffelmeyer, an assistant professor in the Department of Community and Environmental Sociology. “Farmers are really struggling because they often have to work off-farm to get health insurance for their families. They may have to drive many miles to find childcare. Recent studies have shown that farmers can feel a real sense of failure and anxiety around not being able to meet the expectations reflected in the images.”

Hoffelmeyer is part of a team looking more closely at this issue through involvement in a multi-institution project called Linking Childcare to Farm Children Safety, which seeks to understand what farm parents do with their children while they work and how these choices impact farm productivity and the safety of their children.

A Collaboration Across Institutions

The Linking Childcare to Farm Children Safety project is co-led by Florence Becot of the Pennsylvania State University and Shoshanah Inwood of The Ohio State University. The project is part of the National Children’s Center for Rural and Agricultural Health and Safety, which is based in Marshfield, Wisconsin, and funded by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

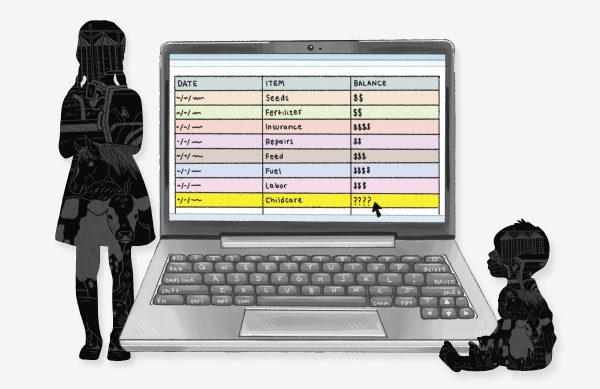

Hoffelmeyer’s portion of the project aims to get a better sense of the environment in which farm parents make decisions about childcare and farming, looking at how farm organizations, extension services, and agricultural agencies regard childcare. This includes whether these organizations consider childcare as part of the labor that goes into running a successful family farm or as a separate issue — more like a personal or household expense. The goal is to understand how these groups are attending to this issue, the broader implications, and, if needed, steps that could bolster support.

“We found a diversity of views of how farm business organizations perceive the centrality of children and families to overall farm viability,” Hoffelmeyer says.

–-–

Hoffelmeyer joined CALS in 2023, a strategic addition to the UW Dairy Innovation Hub’s faculty roster, to focus on public engagement with agriculture. More specifically, as a member of the Hub’s “growing farm businesses and communities” theme area, Hoffelemeyer’s role is to explore public awareness and engagement with broadscale social, economic, and ecological issues that are entangled with agriculture.

Hoffelmeyer (they/she pronouns) is a good fit for the job. Before joining UW, their work focused on how various groups access agricultural resources and how structural inequalities influence food production and environmental sustainability, focusing on rural and urban women farmers; LGBTQ farmers; and farm workers. Now, at UW, Hoffelmeyer will continue this work and also expand into new dairy-focused areas, such as robotics and market concentration. The underlying motivation remains the same. “My driving focus is to improve the agrifood system for everyone, with the goal of serving all farmers and celebrating all people involved in agricultural production,” Hoffelmeyer says.

Hoffelmeyer’s research on women’s farm organizations in the Northeast caught the attention of Florence Becot at Pennsylvania State University. Becot reached out to see if Hoffelmeyer would be interested in collaborating on the “Linking Childcare to Farm Children Safety” project, which launched in fall 2020 with funding from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

By the time Hoffelmeyer joined in 2023 the researchers had already conducted interviews with key informants, focus groups and a photovoice activity with women farmers, and a survey of farm households. In the survey, which is the first national assessment of childcare for the farm sector, over three-quarters of farm families with children under 18 reported that they had experienced childcare challenges in the last two years. Furthermore, three-quarters of farm families surveyed said they believe farm organizations should represent their needs in national childcare policy discussions. And the overall findings were clear: Farm parents expressed the need for childcare support. In particular, they cited a preference for holistic support that serves their household and childcare needs as part of their broader farm business needs.

Hoffelmeyer was brought onto the project to help assess an existing set of interviews conducted with leaders and service providers in the agricultural sector to uncover how these organizations are responding to and supporting farmers’ childcare needs, with a special focus on the gendered dynamics of the situation.

–-–

For the UW portion of the study, Hoffelmeyer and their research assistant are taking a second look at interviews conducted with 36 professionals who provide support and educational opportunities to farmers, including farm safety service providers, farm business planning providers, federal and state-level government agencies, and non-profit farmer organizations. Interviewees come from Ohio, Vermont, and Wisconsin, with one-third from the Dairy State. The interviews reveal a diversity of perspectives and approaches.

“Some farm service providers position the presence of children on the farm and the need to provide childcare as liabilities for the success of the farm business. It’s portrayed as a tradeoff,” says Trish Fisher, a Ph.D. student studying community and environmental sociology, who conducted the analysis. This was the majority view, in fact.

“I think it’s the health and safety of the kids on the farm versus the financial productivity of the farm,” expressed one farm business organization representative. Fisher and Hoffelmeyer shared this paraphrased remark from an interview to illustrate the tradeoff perspective in a recent presentation.

The initial analysis of the interviews, published in 2022 by Becot and colleagues, found that, when it comes to farm business planning, most interviewees don’t incorporate childcare. Instead, children are considered personal or household expenses, and, therefore, outside the purview of a farm business plan. However, some organizations treat farm viability and the flourishing of the farm family like a united enterprise, considering childcare and health care as integral parts of farm business planning.

In cases where childcare was not actively considered, respondents cited several reasons. They explained that childcare was beyond the scope of their organization’s mission, and they expressed having a lack of tools and resources on the topic area. In other cases, they believed other types of professionals or groups were already supporting farmers in this way and are in a better position to handle it. Still others reported a lack of demand from their constituents.

To build on these findings, the Wisconsin team was asked to dig into the interviews anew, exploring what was shared through a gender lens.

“A lot of these farm service organizations shared the sentiment that childcare for farm families is important, but their male farmers are not bringing those issues to the table,” Fisher says. “I don’t want to paint the wrong picture — this isn’t a burden that is universally borne by women. Our collaborators involved in other areas of the overarching project have published findings showing that male partners are often also very worried about child safety. Everybody is extremely stressed about it.”

At the same time, it’s clear that gender dynamics are playing a role.

“I think one of the main themes so far is that, within these organizations that serve farmers, childcare is largely seen as a women’s issue rather than a business issue,” says Fisher. “So childcare, if it’s being addressed, is often being addressed in contexts that are specific to women farmers.”

–-–

The overall findings show there’s a need that’s not being met adequately —at least, not yet.

“We’ve identified a number of structural and resource constraints that serve as barriers for these organizations to address the childcare issues being faced by their constituents,” Hoffelmeyer says.

These findings are not surprising to Hoffelmeyer, who has spent a lot of time thinking about underpaid and undervalued labor on farms. “A real issue in farming more broadly is that, while we often take ownership very seriously, we’ve never taken labor seriously,” they say. “If you look back, historically, women have often done a lot of unpaid and invisible labor, whether it was animal rearing or bookkeeping.”

Similarly, the tasks involved in social reproduction — such as raising kids, taking care of the elderly — often fall to women and are likewise unpaid and invisible, Hoffelmeyer notes. Yet these are critical tasks required by society to keep families going and for the succession of farms.

“We tend to value economic involvement more than household involvement [when it comes to ensuring the viability of family farms],” Hoffelmeyer says. “Because of this, there’s a lack of support for the people who most acutely feel the need for childcare support. Oftentimes, that’s women because of social norms, what people are expected to do.”

The next steps involve raising awareness about these issues. For their part, Hoffelmeyer and Fisher shared their initial findings at the 2025 Dairy Summit, a Hub event for farmers, agricultural leaders, and researchers. Hoffelmeyer’s collaborators have also been sharing project findings through research briefs, conversations with federal congressional leaders and national farm organizations, and a traveling picture exhibit created with farm women who participated in the study.

As with most complex societal problems, Hoffelmeyer doesn’t anticipate a quick fix. “In social sciences research, we often go to the root of the problem — looking at how it began,” Hoffelmeyer says. “So, I think instead of offering a solution to a specific problem, we’re really asking how did things get to be this way?

“We actually know how to solve a lot of issues. And we even understand the causes of our problems, broadly, but it’s often the cultural norms, the social expectations, those kind of dynamics that are preventing change. It takes a long time to change power dynamics and inequality and big global issues.”

Yet it’s satisfying work for Hoffelmeyer, doing what’s possible to help ensure all members of the agricultural community are heard, considered, and supported.

This article was posted in Economic and Community Development, Features, Summer 2025 and tagged childcare, Children, Community and Environmental Sociology, farm finance, Farm safety, Michaela Hoffelmeyer.